They have a thing called “happiness hours”, if an employee has done something good, the manager can give him 3 hours that he can leave the clinic and do whatever he wants.

How did the idea of doing a Family Medicine internship in Dubai come about? And why Dubai?

The idea of an international internship came right at the beginning of my residency: I knew I wanted to have another multicultural experience, especially because specialized training in Family Medicine considers the clinical and professional profile defined internationally by WONCA. In an increasingly globalized world, it is essential that family physicians have a broad view of various realities and can easily adapt to any culture. After doing Erasmus in Paris during my final year of medical school, I thought I should choose a completely different destination, on another continent. I wanted to experience another culture and economic reality, where the concepts of the health system could enrich my professional activity.

I chose Dubai because, besides being one of the safest destinations in the world to carry out this “solo” experience, it has a unique multicultural richness and unparalleled resources, marked by continuous advances in technology and innovation in all fields, including health. Thus, my goals were to exchange experiences in healthcare management, to have contact with all types of cultures and their particularities, especially in terms of treatment and physical examination, as well as to discuss working methods that could best serve the patients—goals which, to my pleasant surprise, were all achieved.

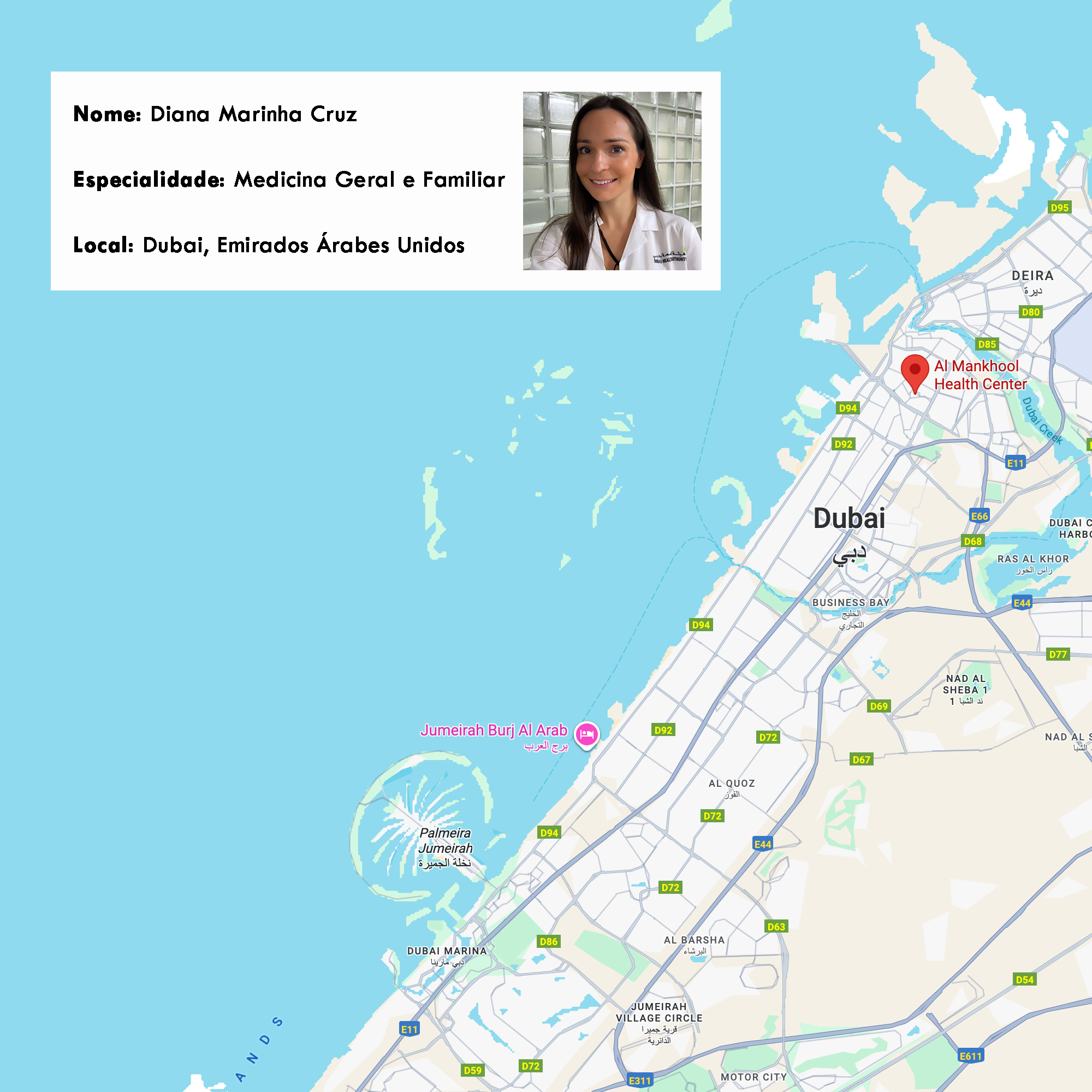

What was the name of the Health Unit where you did your internship, and how was it structured?

My internship was carried out at the Al Mankhool Health Center, part of the Dubai Health Service (DHS), the public system, located in a standalone building with two floors, and comprised of 10 Family Medicine specialists (at least one of them providing video consultations exclusively), working in coordination with 30 nurses (in shifts), 4 clinical secretaries, 2 pharmacists, and 2 security guards daily. In addition, there are specialists in Maternal Health, Child Health, and Development who conduct consultations on a rotating basis, one or two shifts per week, to meet the needs of these specific populations. Although there were no Family Medicine residents at the time, the center contributes to the training of students from the Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine, through which I applied for this internship.

DHS has 14 Primary Health Care (PHC) clinics in Dubai, all operating similarly. In terms of general operation, there are no patient lists assigned to each doctor, nor fixed doctor-nurse teams, though they plan to implement such a model soon. Each doctor sees the patients of the day randomly; however, while I was there, they had started assigning patients to a single doctor, beginning with those over 60 years old and then descending by age.

The health center dates to 1987, so some areas are still divided by gender. The newer centers no longer have this gender division, except in some waiting rooms, which is functionally the case in this center. It has two pharmacies where patients collect all prescribed medications at the end of their consultations, as well as a laboratory for sample collection and four waiting rooms. Additionally, there is an emergency room, two treatment rooms, a pediatric specialty area, and a radiology specialty area with two ultrasound rooms and one X-ray room. Finally, there are also prayer rooms.

In the pediatric area, there are Family Medicine doctors who have completed fellowships in maternal and child health, who see pregnant women and children with suspected autism or ADHD, together with psychologists and social workers. Once a diagnosis is confirmed, the patients are referred to specialized centers for complementary therapies and follow-up. This pediatric area includes a breastfeeding room, a vaccination room, a reading room, and five medical offices.

Were the patients in this Health Unit predominantly native citizens of the United Arab Emirates or immigrants to Dubai? From which countries?

The health centers serve a multicultural community, where less than 10% are natives, the Emiratis. The majority are of Indian and Pakistani nationality, among many others in lower percentages.

In what language were the consultations conducted?

Preferably in Arabic and English. I rarely encountered an Arab patient who did not speak English; these were essentially elderly individuals, but they were always accompanied by someone bilingual, which is increasingly the norm in the country.

How is the Health System organized in Dubai? Is it more similar to Beveridge or Bismarck models?

Dubai’s health system is more similar to the Bismarckian model, though it is a hybrid. There is funding through health insurance, mandatory for all residents since 2014 (employers must provide insurance for their workers). However, Emirati citizens have free or subsidized access to public healthcare.

The health sector is regulated by the state, through the Dubai Health Authority (DHA), which oversees both public and private services, as well as licenses, clinical regulations, and medical standards.

For example, medication is completely free for natives and residents (sometimes with drones delivering medication at home, in some cases shortly after the request). Non-residents pay for services in full, usually immediately after service, typically through insurance. Previously, all health services were free, but fees were introduced due to the medical tourism boom.

For economically disadvantaged individuals who cannot pay, foundations such as the Jalila Foundation and the Red Crescent fully fund all health care. Thus, no one is left without access to the medical care they need. As a curiosity, thanks to these foundations, to which everyone with greater means donates (it is part of the culture and religion), there are no homeless people. This is something to reflect on in our society, increasingly affected by inflation and the climate of war at Europe’s doorstep, but also by the growing lack of empathy for others’ needs.

Can you describe a typical working day for a Family Physician in Dubai?

In the public service, shifts run from 7:30 am to 3:30 pm, 2:00 pm to 10:00 pm, and weekends, on a rotating schedule, totaling 40 hours per week. In the private sector, there is more flexibility, as in Portugal.

There is an official DHS app where users make all requests, including appointment bookings. Alternatively, and rarely, requests are made by phone. It is also possible to schedule a video consultation via the app. The goal is to reduce paper consumption and fully digitize the system, so the health center no longer has a printer, and they really don’t need one.

Walk-ins, without appointment (similar to our open consultations), are scheduled from 7:50 am, with the number of consultations varying daily depending on each doctor’s availability, but with at least 4 slots per day. All appointments, scheduled or not, are 20 minutes per patient. Consultations are not classified by type; they emphasize that “they treat the whole patient, not the disease”. It makes perfect sense for me. Each doctor has 2 slots blocked in their agenda, a 20-minute break mid-morning, and a 30-minute lunch break per day, all included in working hours. All patients check in at reception upon arrival and, regardless of whether they are acute or scheduled, are seen by the nurse, who writes the reason for the visit and collects vital signs before each medical consultation.

There are Diabetes and Hypertension clinics, specialized centers where all patients with these conditions are seen once a year for a full check-up, specific screenings (such as retinopathy and nephropathy), or if they are decompensated. All other management and follow-up are done at the health center where they are registered by area of residence.

At the center, routine or urgent analyses are collected and sent to the hospital for processing, with results available the next day. There is X-ray and ECG (performed by technicians, with immediate results). There are three centers providing mammography, to which women eligible for organized screening or with clinical need are referred.

There is also family planning like ours, including premarital consent (in line with local culture and law), and all contraceptive methods are available and used according to clinical need or couple preference. They perform prenatal diagnostics (PND), offering the possibility to terminate a pregnancy in the case of trisomies. In cases of thalassemia in carrier couples, the possibility of termination or IVF is offered. HPV vaccines are available for women at the same ages as in the Portuguese national vaccination plan, and for men it is still optional.

Regarding organized screenings, there is also cervical cancer, colorectal cancer with FIT or colonoscopy at the same ages as in Portugal, but mammography starts at age 40 every two years.

There are smoking cessation centers, and the public health department visits schools periodically to weigh children and conduct vision screening.

Home visits are done every three months and, between these, nurses conduct visits and video consultations with physicians. Nurses also carry the necessary equipment and collect samples during home visits. I had the opportunity to attend one visit, and I felt extremely well received from the Arab family.

I saw all people caring other people with happiness and kindness, which should be the point of health care everywhere – but only possible with motivated professionals and adequate working conditions.

Comparing Family Medicine practice in Dubai and Portugal, was there anything that made you think “I wish it were like this in Portugal”?

Indeed, the resources are very different from our reality. Here, we do a lot with little. There, with a lot, they do more and better. For example, waiting times for an appointment are always less than 10 days. These are monitored by indicator software, tracking mainly waiting times and numbers of appointments; if these rise, the government immediately hires more professionals to reduce waiting days as quickly as possible. At hospital level, waiting times are longer, but still always under 3 months.

The system is very unbureaucratic and includes the issuance of essential medical certificates, for example, for patients to have priority if they have mobility difficulties. There are no certificates for driving licenses: the responsible center itself conducts the necessary ophthalmological and medical assessments. Work incapacity certificates are issued by the doctor who makes the diagnosis or performs surgery, estimating at that moment the required recovery time and defining it in the initial certificate (almost always the only one), whether days, weeks, or months. The user receives their usual pay in full, regardless of reason or certificate duration.

They use Epic system software and SALAMA, where all user data are stored, as well as an updated photo, with numerous tabs to consult the entire clinical history. This colorful and intuitive software is extremely comprehensive and minimally bureaucratic—once again, far superior to our SClínico®.

I also had the honor of being invited by the head of Family Medicine specialists and PHC clinics in Dubai to visit the best, largest, and most recent PHC clinic in Dubai, Umm Suqeim Health Center. I was given a full guided tour and was absolutely amazed by the facilities and organization, which I would love to see possible in Portugal. For example, in addition to the latest imaging equipment, it has a fully equipped emergency room (like those in hospitals), a rehabilitation gym with all kinds of equipment and a view for Kite Beach, ophthalmology offices with all the necessary specialty equipment, and dental offices with specialist dentists. All sorts of health professionals work there—psychologists, nutritionists, physiotherapists, dentists, among others—all within the public healthcare system.

And the opposite: “In Portugal, this is better”?

The doctor-nurse family team system, with their patient lists, is unequivocally a great advantage for me, although it is being implemented there and, conversely, in Portugal is being lost, as the concept of a stable family team over many years is becoming less likely due to the current reality of the National Health Service (SNS).

Furthermore, in Portugal, only Obstetricians and qualified Radiologists can perform maternal ultrasound, which I believe makes more sense. In Dubai, pregnant women are followed up at health centers unless considered high risk, in which case they are referred to the local hospital. There, family doctors can do fellowships in maternal health and ultrasound, being qualified to follow low-risk pregnancies at the health center from preconception to 34 weeks (then they are referred to the hospital for delivery), and ultrasounds and analyses are conducted at the center itself. If routine appointments with qualified doctors are not available in a timely manner, even low-risk cases are referred to the hospital for ultrasounds.

And in terms of work-life balance? In your opinion, after this experience, where does a family physician have a better balance: Portugal or Dubai?

Undoubtedly, Dubai offers a better balance, especially because of the workload during working hours. For example, with bureaucracy: if a report or document is needed, a consultation slot is blocked in the doctor’s agenda for this purpose, meaning there is no overload for the doctor nor extension of the normal working schedule, whatever the reason. I highlight the mandatory breaks between consultations and the lunch hour, which are actually respected, as well as an IT system that is genuinely helpful. Moreover, professionals are valued and recognized, which contributes to personal fulfillment and quality of life. For example, they have a thing called “happiness hours”, if an employee has done something good, the manager can give him 3 hours that he can leave the clinic and do whatever he wants, it’s like permission to leave early and they call him hours of happiness, something absolutely impossible in Portugal nowadays. I saw all people caring other people with happiness and kindness, which should be the point of health care everywhere – but only possible with motivated professionals and adequate working conditions.

This experience was extremely useful, both for the clinical exchange and the clarification of doubts I had prior to the internship, as well as for breaking down fears related to cultural differences: a doctor is always a doctor, wherever they are needed most.

I would like to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Mouza AlMehairi and Dr. Shatah AlSuwaidi for the kindness, gentleness, and care with which they received, integrated, and guided me through this enriching experience. Shukran!

Interview conducted by Carlos Martins